Imagine this scene, which is playing out in clinics and hospitals around the world every day:

A medical resident sees a patient with a complex set of symptoms. After the visit, they discreetly pull out their smartphone, type a few prompts into a generative AI chatbot, and within seconds, receive a polished, persuasive differential diagnosis and management plan. They copy it directly into the patient’s electronic health record.

Across the room, their supervising physician watches this unfold. A wave of questions floods their mind: “What prompts did they use? Are they questioning the AI’s output or just accepting it? Can I trust this? Is this the future of medicine… and if so, what is my role now?”

This vignette captures the central dilemma facing healthcare education today.Artificial intelligence is no longer a future concept in healthcare — it’s here, now, embedded in classrooms, clinics, and even at the bedside. Large language models (LLMs) and other AI systems can generate differentials, interpret images, and draft clinical notes with human-like fluency. That creates remarkable opportunities — and unprecedented risks — for medical education.

A recent New England Journal of Medicine article (Abdulnour, Gin, Boscardin, 2025) shines a light on something we must urgently confront: how do we train and supervise the next generation of clinicians in an AI-enabled world? Will we use AI to create the most highly efficient, yet critically deficient, generation of clinicians in history?

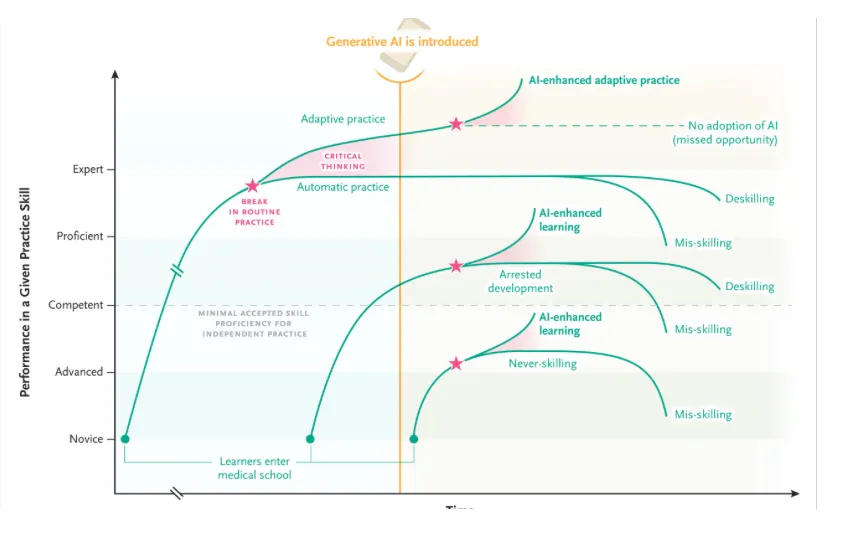

The authors of the NEJM paper, Abdulnour, Gin, and Boscardin, lay out the stark risks of getting this wrong:

- Deskilling: The loss of hard-won clinical reasoning abilities as we offload thinking to machines.

- Never-Skilling: A failure to ever develop essential competencies in the first place, creating a permanent dependency.

- Mis-Skilling: The unconscious adoption of AI’s errors and embedded biases, which could systematically perpetuate diagnostic inequities.

At the heart of this challenge is critical thinking. In a world where AI offers answers without transparent reasoning, clinicians must develop the ability to pause, reflect, and interrogate those outputs.

Critical thinking enables what educators call adaptive practice — the ability to shift between efficient routines and flexible, innovative problem solving when the unexpected arises. In other words, it’s the difference between blindly trusting AI and thoughtfully integrating it.

The most alarming research shows that overreliance on AI tools has a significant negative correlation with critical thinking abilities. In one study, users who blindly adopted AI outputs actually performed worse with AI than without it on complex tasks. This “unengaged interaction” is a direct path to intellectual atrophy.

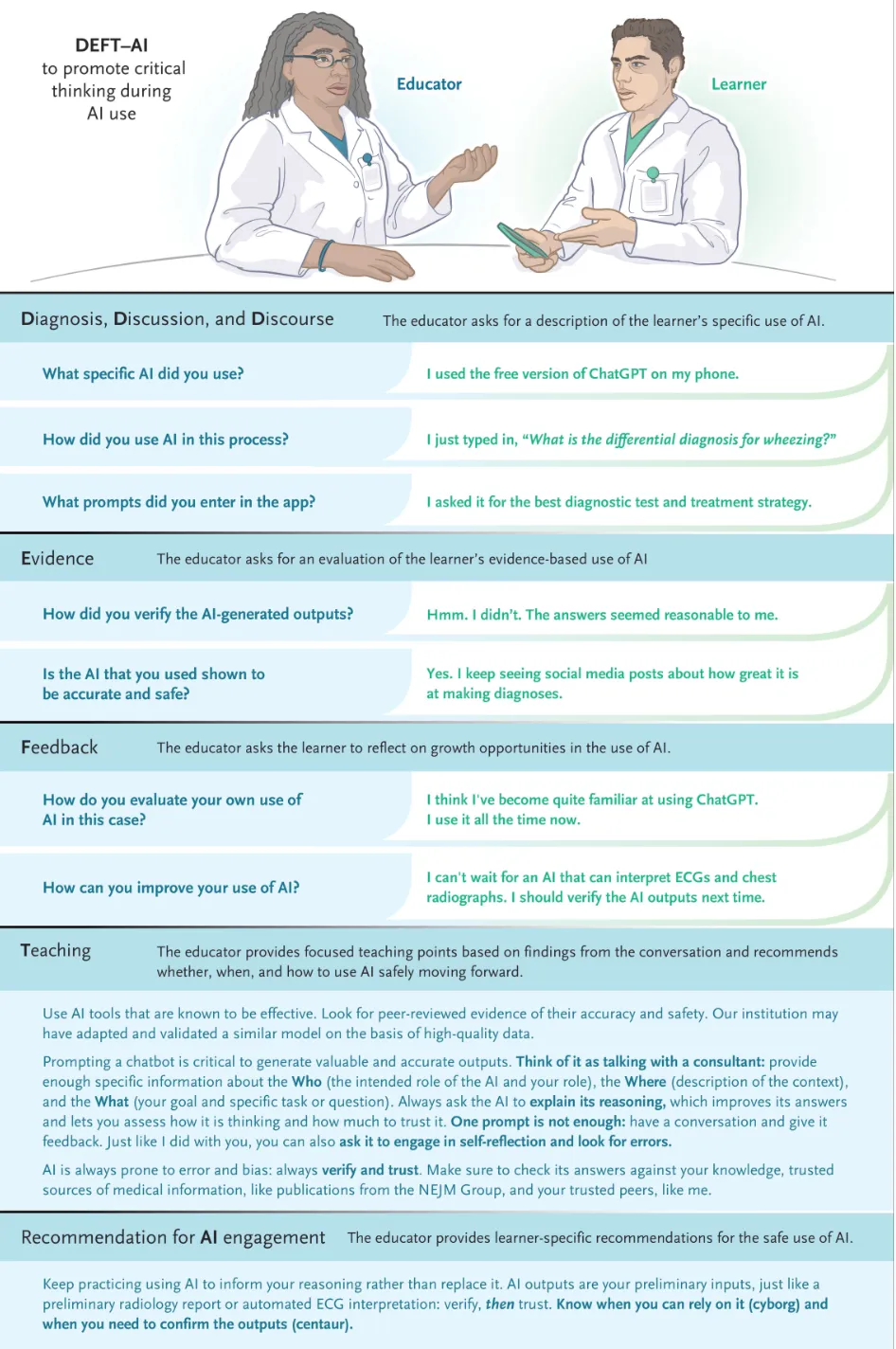

But this is not a reason to ban AI. That ship has sailed. The imperative is to integrate it intelligently. The authors propose a brilliant, practical framework for clinical supervisors called DEFT-AI. It’s a structured way to turn every AI interaction into a teachable moment that fortifies, rather than undermines, clinical judgment.

A New Role for Clinical Educators

The NEJM authors make a powerful point: for the first time in history, learners may be more adept with a new technology than their teachers. Faculty may find themselves supervising residents who are already AI-literate. That inversion is uncomfortable, but it’s also an opportunity.

Educators must embrace a shared learning model, where teachers, trainees, and even patients co-explore the limits and possibilities of AI. Communities of practice — grounded in humility and curiosity — are essential.

And supervision itself needs a new framework.

DEFT-AI works like this:

- Diagnosis & Discourse: The educator probes not just the learner’s clinical reasoning, but their AI interaction. “What prompts did you use? How did you challenge the AI’s output?”

- Evidence: The learner must justify their conclusions using medical evidence and also demonstrate AI literacy—understanding the tool’s limitations and the evidence (if any) supporting its use in this context.

- Feedback: Guided self-reflection on what the learner missed and how their use of AI helped or hindered the process.

- Teaching: Tailored instruction to fill knowledge gaps and improve prompting strategies.

- AI Recommendation: A final judgment on how the learner should engage with AI for this type of task going forward: with direct supervision, indirect supervision, or independently.

This process helps learners navigate two distinct styles of AI use, which the authors brilliantly term Centaur and Cyborg behaviors.

- The Centaur strategically divides tasks. They use AI for ideation or drafting but rely on their own judgment for final diagnosis and decision-making. It’s a partnership.

- The Cyborg intertwines their work with AI at every step, co-creating solutions in a continuous feedback loop. This is powerful for low-risk tasks but dangerous for complex reasoning.

Adaptive expertise—the ultimate goal—is the ability to fluidly shift between these modes based on the task and the risk.

The most profound shift, however, is for us, the educators. We are often less AI-literate than our learners. We must abandon the pretense of being the sole expert in the room and embrace a shared learning model. Our new role is to be the guide, the critical thinking coach, the one who instills the “verify and trust” paradigm.

We must teach our students that an AI interaction is defined as “a moment when a computational artifact provides a judgment that cannot be traced, prompting a leap of faith.” Our job is to teach them to never make that leap blindly.

The future of medicine isn’t about humans versus AI. It’s about humans augmented by AI. But that augmentation only works if the human core—our critical thinking, our empathy, our ethical judgment—is stronger than ever. The DEFT-AI framework gives us the tools to build that core, ensuring that the clinicians of tomorrow are not just efficient data processors, but the most capable, adaptive, and thoughtful healers we have ever produced.

Promoting AI Literacy in Medicine

Ultimately, we need to train both educators and learners in AI literacy. That includes:

- Recognizing an “AI moment” — when a leap of faith is required

- Critically appraising AI tools and outputs with evidence-based frameworks

- Learning effective prompting strategies (“prompt engineering”)

- Practicing reflective oversight instead of blind adoption

This is not optional. Without it, we risk producing a generation of clinicians who can navigate apps but not ambiguity.

The Way Forward

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: AI is here to stay in medical education. Learners are already using it — often unsupervised. Pretending otherwise won’t protect patients.

Instead, we must:

- Redesign curricula to explicitly integrate AI use, critical appraisal, and ethical supervision.

- Develop faculty who are confident enough to teach while they learn.

- Build governance structures to validate tools, monitor outcomes, and protect against bias.

- Adopt a “verify and trust” mindset — never replacing human reasoning with AI, but strengthening it through careful integration.

The age of AI in medicine is not about replacing clinicians. It’s about reshaping what it means to think, decide, and care in a world of probabilistic, opaque, but powerful tools.

As educators, we face a choice: let AI deskill our learners, or harness it to build smarter, more adaptive, more human clinicians.

The time to act is now. The AI co-pilot is in the cockpit. It’s our duty to ensure the human pilot remains firmly in command.

Your thoughts? How are you seeing AI used in your clinical or educational environments?

0 Comments